“Try it with water,” said my guide from The Lakes Distillery, pointing to the small pitcher filled with the clear, distilled liquid in the centre of our table.

“Try it with water,” said my guide from The Lakes Distillery, pointing to the small pitcher filled with the clear, distilled liquid in the centre of our table.

“I don’t need to,” I said. “I can handle this as it is.” I lifted the glass of whisky and swilled it around gently, as a gesture of my confidence.

“That’s not the point,” the guide replied. “Whisky tastes better if you add water. Have a go. You’ll see what I mean.”

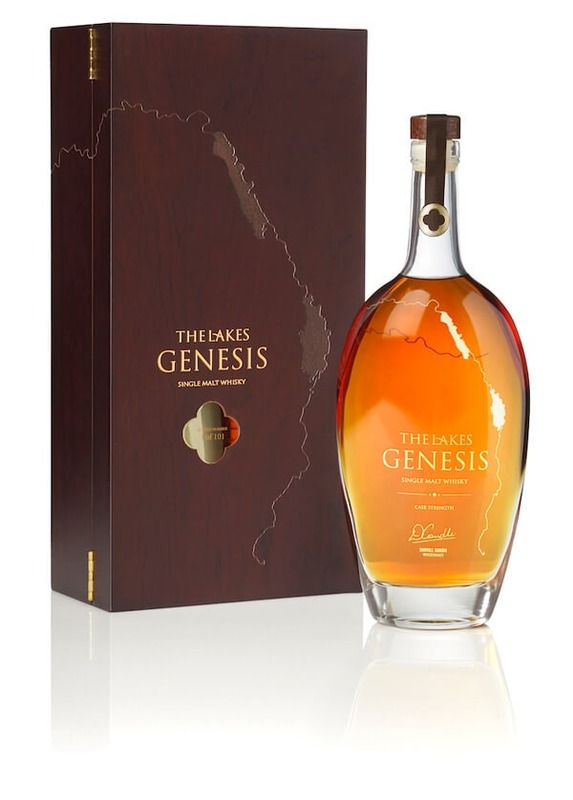

The distillery is one of English whisky’s newest additions, housed in now renovated farmhouse buildings at the top end of Lakeland’s Bassenthwaite. It is a classy operation aimed at the premium end of the market. Its first bottle, Genesis, was sold in 2018 for an astonishing £7900. I knew little about whisky when I arrived at the distillery, it was a drink that I often avoided, but after its Distillery Tour and Tasting, I knew plenty more.  I had learned something of its language – pot ale, charge, draff and wort – I had learned the importance of the whisky-maker, the history, and stories. I was now at risk of becoming a serious whisky bore.

I had learned something of its language – pot ale, charge, draff and wort – I had learned the importance of the whisky-maker, the history, and stories. I was now at risk of becoming a serious whisky bore.

The drink, which is distilled from various grains, although normally barley, is more than a pale brown alcoholic liquid. It has medicinal benefits and adds serious value to the country’s coffers. Scotch whisky alone earns the UK economy £5.5 billion annually, a sum that is rising year-on-year. It contributes 21% to the value of all UK food and drink exports. Whisky is going nowhere in a hurry.

But the spirit needs water both to make and drink. Whisky-making in the UK demands more than 60 billion litres of water each year, 75% of which is used as coolant. For every litre of whisky produced, 47 litres of water are needed. The Lakes Distillery takes its supply from the nearby River Derwent, all of 150 metres distant, and is also drilling its own borehole.

The water, which ends up in a bottle of Lakes whisky, and next in my glass, starts off life high in the Lakeland fells. This is said to be Sprinkling Tarn, 25 kilometres to the south, which feeds the young River Derwent. The isolated, six-acre tarn is the most perfect place to wild camp, although it is said to be the wettest spot in England thanks to the five metres of rain it receives each year. It is also the only UK home to the vendace, the rarest freshwater fish in the land. I know they are there because I saw one. And no, I did not eat it.

The water, which ends up in a bottle of Lakes whisky, and next in my glass, starts off life high in the Lakeland fells. This is said to be Sprinkling Tarn, 25 kilometres to the south, which feeds the young River Derwent. The isolated, six-acre tarn is the most perfect place to wild camp, although it is said to be the wettest spot in England thanks to the five metres of rain it receives each year. It is also the only UK home to the vendace, the rarest freshwater fish in the land. I know they are there because I saw one. And no, I did not eat it.

Water is not only essential for whisky making, it is vital to the final drink. Whisky matures in oak casks and, if stored for several years, the alcohol partly evaporates through the cask walls. Each year, evaporation causes the alcohol content of whisky to decline by almost 1%. Even so, by the time a Lakeland whisky reaches the bottle, it will contain approximately 60% alcohol. Such strength can numb taste buds in an instant, so dilution with water is encouraged.

Whisky buffs hold serious discussions about the type of water to use, as well as how much should be added. Whatever type is chosen, distilled, spring or tap, dilution reduces the drink to about 40% alcohol. Research has shown that the lower the content of alcohol, the more likely it is that flavour molecules will rise to the surface and improve a whisky’s taste.

Whisky buffs hold serious discussions about the type of water to use, as well as how much should be added. Whatever type is chosen, distilled, spring or tap, dilution reduces the drink to about 40% alcohol. Research has shown that the lower the content of alcohol, the more likely it is that flavour molecules will rise to the surface and improve a whisky’s taste.

“How much do I put in?” I asked the guide.

“Your call,” he replied, and then pointed at the pitcher. “You see that glass pipette?”

I nodded. I could see the tubular shape leaning against the inside of the small jug.

I nodded. I could see the tubular shape leaning against the inside of the small jug.

“Use that to add the water,” he instructed.

Being a novice, I was still confused.

“Five drops should do it,” he added.

So I did. I placed five drops from the pipette into the whisky glass like a scientist. One…two…three…wait for the explosion…none…four…wait again…five. The guide looked on approvingly.

“That’ll be fine,” he said, once the fifth drop had sploshed into place, adding, “no need for ice. That will simply dilute it further.”

“That’ll be fine,” he said, once the fifth drop had sploshed into place, adding, “no need for ice. That will simply dilute it further.”

I nodded. In the distillery shop I had seen the whisky stones, cubes of solid soapstone that are non-porous, tasteless and odourless. The experts use them to chill their whisky without altering its flavour.

Dilution done, drink prepared, I picked up my glass.

“Slowly,” said the guide when he saw I was about to gulp. “Sniff, sip and savour. Think about the taste.”

Which I did. And you know what? It was wonderful, even to a teetotaller. Maybe I should take up drinking, especially now that Lakeland has its own whisky.

Do not miss their tour.

More information

The Lakes Distillery – Setmurthy, near Bassenthwaite Lake, Cumbria, CA13 9SJ. Tel: 017687 88850

Getting there

Drive: 318 miles from London; 126 miles from Manchester; 34 miles from Windermere

Rail: The nearest local train station is Aspatria, operated by Northern Railway. The nearest mainline train station is Penrith on the west coast mainline.

Bus: The Lakes Distillery has its own bus stop on the Stagecoach X4 route from Workington to Penrith. The schedule can be found here.

Parking

There is free parking on site for up to 90 cars and 5 coaches.

Accessibility

Wheelchair users are welcome but motorised wheelchairs are not permitted on the tour. There is a wheelchair lift between floors although it cannot accommodate Motability scooters. A courtesy manual wheelchair is available on request and carers are welcome for free. Enquire at the time of booking.

Staying there

Eating there

Distillery Bistro – on site at the distillery with indoor and outdoor seating areas. Tel: 017687 88850

The Pheasant – Bassenthwaite Lake, Cockermouth CA13 9YE. Tel: 017687 76234

Do not miss

Lake District Wildlife Park – Coalbeck Farm, Bassenthwaite, Cumbria CA12 4RD. Tel: 017687 76239

Alpacaly Ever After – Tel: 017687 78328

Lake District Off-Road – Water End House, Portinscale, Cumbria CA12 5UB. Tel: 017687 73880