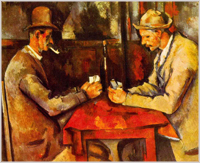

Although Manet and Renoir were in the vanguard of the French impressionist movement that swept the objections of traditionalists aside during the heady decades of the 1870s and 1880s, Paul Cézanne was the latecomer who most understood its potential. ‘I want to make impressionism solid and lasting’, he said, and became just as prolific a collector of prints and reproductions of the genre as an artist in his own right.

Although Manet and Renoir were in the vanguard of the French impressionist movement that swept the objections of traditionalists aside during the heady decades of the 1870s and 1880s, Paul Cézanne was the latecomer who most understood its potential. ‘I want to make impressionism solid and lasting’, he said, and became just as prolific a collector of prints and reproductions of the genre as an artist in his own right.

Cézanne belongs to that select group of painters who can be exhibited anywhere and guaranteed to draw the crowds. He would have been gratified, but not at all surprised, to find his own work on display in the Museum of Fine Arts at Budapest, in a new exhibition entitled Cezanne and the Past: Tradition and Creativity. Most of the great galleries of the world are contributing pictures, and the museum is attempting to analyze the development of impressionism in tandem with Cézanne’s own subtle changes in style.

What characterizes impressionist paintings above all is their adherence to small, thin brush strokes of unmixed, primary colours to simulate actual reflected light; and the capture of movement as a crucial dimension of human experience. Common, ordinary subject matter is elevated into a compelling impression of a scene or object, often seen from unexpected visual angles.

If Cézanne’s half-Italian father had had his way, Paul would have been either a hatter or a banker. The huge success of the family’s felt hat business in Aix-en-Provence led to his father establishing a bank, where Cézanne worked from 1859 to 1861 while studying law at Aix. It was only in April 1861 that his father reluctantly agreed to help him make a career in art and sent him to Paris.

Cézanne returned regularly to Aix and the south of France but the town of his birth in 1839 has only a few of his paintings and none of his best works. It does however possess his last studio, preserved after Cézanne was caught out in a storm in October 1906, when he carried on with his latest canvas for a couple of hours, and died a few days later from pneumonia.

Cézanne returned regularly to Aix and the south of France but the town of his birth in 1839 has only a few of his paintings and none of his best works. It does however possess his last studio, preserved after Cézanne was caught out in a storm in October 1906, when he carried on with his latest canvas for a couple of hours, and died a few days later from pneumonia.

The spirit of the master lives on amidst the props Cézanne used for his paintings and all the bric-a-brac of an artist indifferent to worldly clutter. You almost expect the old boy to come in from the garden, clutching a half finished bottle of wine or brandy, as though awakened abruptly from an afternoon snooze.

Museum of Fine Arts

Museum of Fine Arts

Budapest, Hungary

Visit website

Cezanne and the Past

is open from 26 October 2012 to 17 February 2013.

For hotel breaks to Budapest, Silver Travel Advisor recommends Regent Holidays.