Cragside was originally built on a bare rocky hillside which has been transformed by the planting of over seven million trees. There are over 40 miles of footpaths and “waymarked walks.”:https://nt.global.ssl.fastly.net/documents/maps/1431729756412-cragside.pdf

The Visitor Centre overlooks Tumbleton Lake, which was formed by damning the Debdon Burn. There is a lovely walk along the burn towards the classic viewpoint of the house with the Iron Bridge.

The bridge is a very elegant structure dating from 1874 and spans the burn on three arches. It has recently been restored and again allows access to the rock gardens and the house.

The rock gardens are one of the largest in Europe and huge boulders fall down the hillside below the house. They are planted with small trees, shrubs and heathers and a network of footpaths allows visitors to explore.

Beyond the house is the pinetum. This was a Victorian symbol of wealth and status. Every stately home owner aspired to one as Victorian plant hunters brought back an increasingly wide range of species from around the world. The Cragside pinetum concentrates mainly on North American conifers. Rustic wood bridges cross the Debdon Burn.

The Formal Garden is a 20 minute walk from the house and, constructed on a south facing slope, and is a sun trap. By the entrance is the clock tower which was built in the Gothic Revival style in 1860. The bell could be heard across the whole estate and controlled life on the estate with a bell signalling the start and finish of work for the day and also breaks for meal times. The mechanism allowed for different striking times on Saturdays and Sundays.

The formal gardens are terraced on three levels. On the top terrace is the massive glass orchard house, built around 1870, and restored at the end of the C20th. There was great status in growing a wide range of hardy and tender fruits. A boiler in the basement provided heat. Plants were grown in large terra cotta tubs on rotating cast iron bases, unique to Cragside. These were powered by electricity generated on the estate and ensured plants were turned one a day to encourage even growth and ripening of the fruit.

The terraces fall down the hillside with views across to the Simonside hills and Rothbury. The Garden Cottage is now a self catering holiday home. On the lowest terrace is an elegant cast iron loggia, with a small pond.

Armstrong was a very foresighted inventor who realised water could be used to power hydraulic lifts for use in his heavy industries on Tyneside. He was one of the first to realise its potential for the generation of electricity for domestic purposes. The Debdon Burn was dammed to form Tumbleton Lake as a water store. The Black Burn was dammed to form another five lakes in the hills above the house. with a wooden flume bringing water from the hills to feed into the lakes.

Tumbledon Lake provided the head of water needed for the Pump House which contained a hydraulic pump which pumped water to a small reservoir above the house. Water also powered a small turbine which provided electricity to light the house. During the day it was also used to operate the estate sawmill.

By the power house is a modern Archimedes screw. These were originally designed to raise water, but this is now working in reverse to generate electricity. Water from Tumbledon Lake enters the top of the screw and pushes down on the blades inside. These turn and the rotational energy is used to drive a generator. The electricity is now being fed into the supply for teh house and it is estimate it can provide enough to light all the lights in the house again.

As the demand for electricity grew, the Pump House could no longer meet demand. A new Power House was built further down the burn in 1886 with turbines powered by water from Nelly Moss Lakes in the hills above the house.

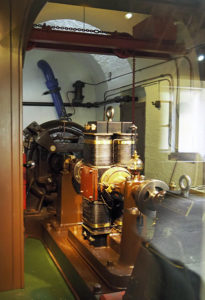

The original turbines and dynamos can still be seen. To maintain the power supply at peak times, a second dynamo was added connected to a set of storage batteries.

During prolonged periods of dry weather the water supply from Nelly’s Lakes became unreliable, so a gas engine was later installed to drive either or both of the dynamos.

The Power House had to be manned at all times by the ‘caretaker of the electric light’. There was a separate control room which was kept warm and dry. This housed the switchboards and solenoids controlling demand. He was connected to the house by telephone.

Footpaths are signed but beware, the estimates of distance can be misleading. When I set off from the formal gardens for the power house, it was signed half a mile. After walking for ten minutes, the next sign still said half a mile. Another five minutes, that was down to one third of a mile, but this was one of the longest third of a miles I’ve walked….