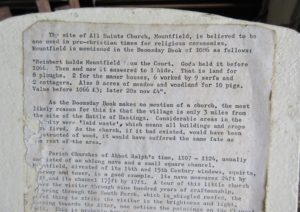

All Saints Church in Mountfield dates back to the 12th century and would have replaced whatever structure stood there previously, probably made of wood.

Mountfield is a small village lying between Battle and Robertsbridge in East Sussex and is mentioned in the Doomsday Book – “ Reinbert holds Mountfield from the Court, Goda held it before 1066. There is enough land for 8 ploughs, 2 for the manor house, and 6 worked by serfs and 2 cottagers. A further 8 acres of meadow, and woodland for 10 pigs.”

We came upon the church after seeking out a nearby gypsum mine, material used to manufacture plaster, plasterboard and cement. My husband had worked there as a student in the early 60’s when studying mining. The mine was set up in the woods and underground workings spread over a wide area beneath the Sussex landscape. Later, a large manufacturing plant was set up.

All Saints church caught our eye because of its lovely position with views of fields and woods across the valleys each side. It blends in with the countryside and inside, where there is plenty of light, there is an air of modesty and simplicity.

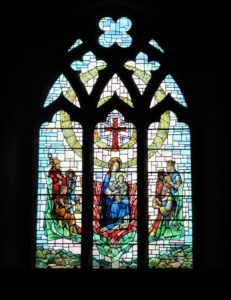

The present church, essentially Norman, has stood there for about 900 years. The nave and chancel date from the early 12th century and the tower was added towards the end of that century. A few of the original windows survive; others were inserted in the 13th 14th and 15th centuries.

The nave has a pointed wagon roof with ‘hammer beams’ and moulded wall plates of the 15th century. The chancel roof is concealed by a plaster ceiling.

As you enter the church you immediately see the second largest font in Sussex. Norman, dating from the 12th century, it is hewn from a single block of stone. The carved, side panels date from the 16th century and depict foliage, fleur-de-lys, tudor roses and scallop shells (symbol of St James of Compostello In Spain and worn by pilgrims who go there). The rim of the font has marks of staples for locking it as ordered by Archbishop Boniface of Canterbury in1236.

The north wall of the church is pierced by 3 windows, the left and middle one dating from the 12th century. The third is much larger and is from the 15th century.

Murals on the chancel wall were discovered during restoration. Almost all the twelfth century painting is lost but a fragment survives on the lower side. From the 13th century comes the pattern of masonry blocks with a daisy like flower in the centre of each block. The sun and framed Ten Commandments below the crossbeam and above the chancel arch date from the late sixteenth century but only two of the Commandments are decipherable. “Thou shalt not commit adulterie” and “ Thou shalt not steale.”

Records show the pulpit was moved in 1880 from in front of the hagioscope to where it is now, in the corner.

The west wall is the original outside wall retained when the tower was added at the end of the 12th century. The clock was installed in the tower in 1905 in memory of Lady Mary Egerton.

There are 3 windows in the south side, also the main doorway to the porch and a number of monuments on the south wall. A door was made to give access to the tower and the west door. The galley on the upper part was added in 1840 when the gallery on the north wall was dismantled and the old pews replaced. In 1896 the new gallery was enlarged to house the Walker organ built and given in memory of Lady Brassey who was a hugely popular Victorian author. Her journey around the world in 1876-7 with her husband Thomas in their luxury steam yacht, resulted in her book ‘The Voyage in the Sunbeam, our Home on the Ocean for Eleven Months (1878)’

As you leave the church the 14th century porch is timber framed on a later brick base and roofed with shingles. The sides are weather boarded. In 1828, it shows in records that the elbow beams in the roof were reversed so that the more weather beaten sides were turned to the inside.

In the churchyard the oldest stone is inscribed “Robert Startup, Innkeeper, Sept. 29th 1705 aged 77 years 10 mos.”

In October 2003, part of the nave floor just in front of the door into the tower was dug up to repair a leaking pipe. The workman dug down about 3 or 4 feet below the present floor and found a layer of ash and scorched earth. Seemingly, there had been a fire of such intensity that the ground itself had burned. What a moment in history to be able to see not only a clod of blackened earth but a glimpse of a time of life in England when it changed violently and forever. Buried and forgotten, the ash of the Saxon church destroyed by fire nearly 900 years ago, until, by chance, a workman revealed it eighteen years ago!

Before 1066, virtually nothing is known about Mountfield, ( Montifelle in the Doomsday Book). We do know it was an ancient site and so, perhaps has an aura of mystery around it.