After a non-stop, three-hour journey we arrived at Assin Manso Ancestral Slave River Park, one of Ghana’s largest markets during the infamous trans-Atlantic slave trade. A panel of murals greeted us at the entrance, depicting various aspects from slave raiding to transportation and despite stiff limbs, we were immediately tagged on to a group of three Afro-American ladies.

We were asked to observe a minutes silence before we stood in the heat for thirty minutes whilst our guide explained the history of the site. Having walked hundreds of kilometers through difficult terrain in shackles and chains from as far as Burkina Faso and northern Ghana, the slaves would have arrived at Donkor Nsuo or ‘the slave river’. Here they would have been bathed, rested, sold and branded before the 32km walk to the dungeons of Cape Coast Castle. Unfortunately our guide’s fast preaching manner, and lecturing crusade was aimed at Afro-Americans wanting to trace their roots with phrases such as ‘you can hear your ancestors’. Unfortunately, his style of delivery completely switched us off and we quickly lost interest.

We then set off through an archway, ‘Welcome to the Ancestral River Park’ and as we saw on our return, ‘Emancipate Yourself from Mental Health’ on the other. Two royal blue wooden doors each depicted a slave in shackles, and we followed a flat broad open path, which would have been thick jungle with poisonous plants.

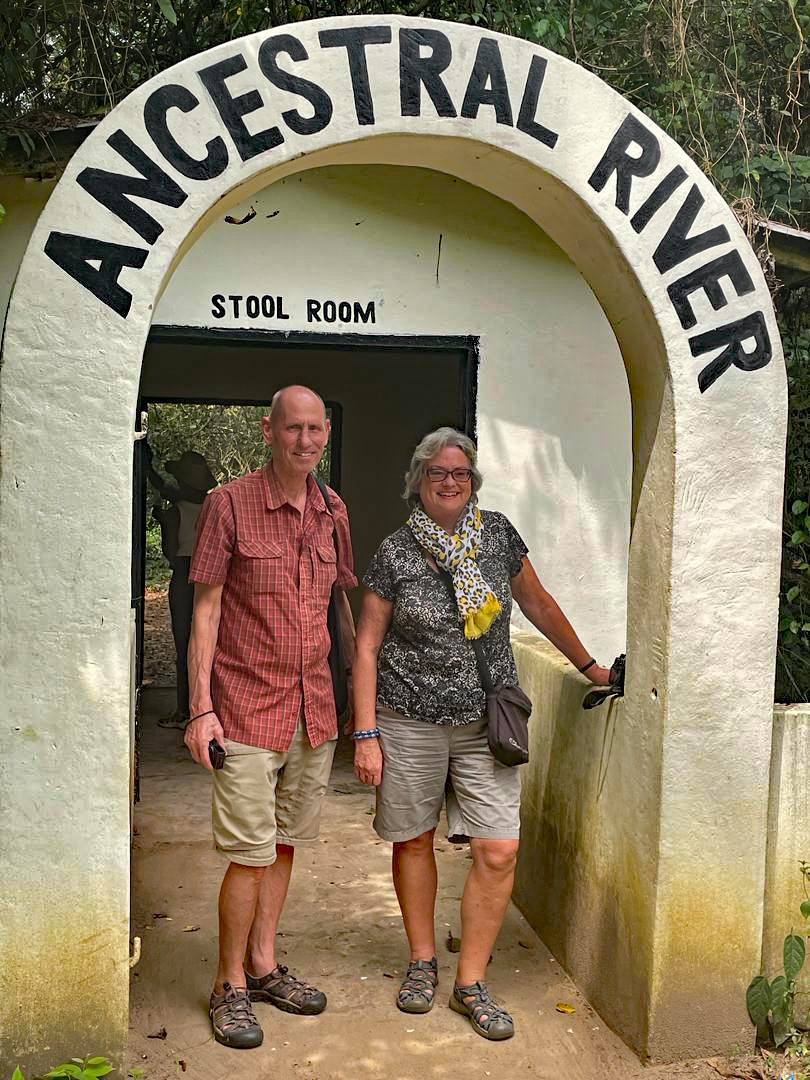

A second archway noted Ancestral River above, led into the Stool Room where on a wall was a list of the paramount chiefs with colourful portraits of the current chief and his predecessor.

We eventually reached the clearing at the confluence of two rivers with one running very fast, although because we were in the dry season, it was relatively shallow. As the slaves would have been shackled, and unable to cleanse their own bodies, they developed a way of washing their neighbour. Once bathed, heads and beards would be shaved with broken glass, and bodies rubbed with shea butter to make them glisten. They would then be sold and branded using hot metals on their bodies to inscribe them with the mark of the new master. Those not sold, due to illness or weakness, would have been dumped into the river.

At the river, particles of gold glistened, and the guide invited us to paddle barefoot, ‘to connect with the soil our ancestors had stood on’, and wash our hands and ears, ‘to touch and hear our ancestors voices’, before saying a prayer. I dipped my hands in the shallow water and whilst the reluctant ladies were being encouraged to remove waterproof sandals, I’m afraid we sloped off.

Back at the entrance, we looked at the Memorial Wall of Return, also known as the Pillars of Recognition, where in exchange for 100 Cedi or £6, you could write your name, city, and the date to indicate the discovery of your roots.

In the Ancestral Graveyard, the remains of two slaves, Samuel Carson from New York and a woman only known as Crystal from Jamaica, had been symbolically returned and reinterred. A third grave contained remains returned in 2019 by the Prime Minister of Barbados, as part of the ‘Year of Return’ campaign: launched by the President in an attempt to attract Africans in the diaspora to Ghana.

Around the perimeter of the centre were portraits on the walls of several notables including WEB du Bois, Booker T Washington, and Ghana’s first president, Kwame Nkrumah.

As we left, we reflected on what a difference a good guide could have made.