The last thing we expected to see, crossing a major ring road into a working class area dominated by a football stadium, was a Jewish cemetery. Even more unexpected was that one of the wealthiest and most magnanimous local residents was responsible for its survival.

We had to visit, not out of curiosity but to pay respects to a community that had once been significant in Iberiabefore suffering the kind of victimisation minority groups in Europe generally now face from the ignorant and prejudiced. The history of this community is essential to understanding the significance of the site.

Fortunately, the cemetery is in the care of a devoted follower, who knew the people responsible for its renovation and reconsecration. It was a pleasure and a humbling educational experience to meet Antonio Valente and discuss with him the history of the Jewish community in Algarve. Without this, the cemetery might become just another curiosity.

Although it dates back only to 1838, the cemetery reflects a much longer history. In the medieval period the Jews were respected advisers, first of the Islamic rulers and then of the Portuguese. They suffered, as Jews did in medieval England and Europe, whenever economic conditions deteriorated and scapegoats had to be found. Look no further for the origins of “The Merchant of Venice”.

Nonetheless, there was a significant Jewish presence in the region until Ferdinand and Isabella ruled Spain. They and their Inquisition applied pressure to Portugal and the Jews were expelled unless they converted to Christianity. Those who went into exile lived in Morocco, a moral tale present day fundamentalists would do well – had they the goodwill – to consider. After the Lisbon earthquake of 1755 the Jews were invited to return to help rebuild the economy but conditions enforced by Spain made this unacceptable to them. Their return was only possible after the Napoleonic war.

Three families became significant in Faro. The head of one made a fortune as a tobacco farmer. He was able to buy land for the cemetery within an area so large it encompassed where the present municipal hospital stands to the north and the football stadium to the south. Next to the stadium, ironically, is a Catholic church. Another purchase was the former convent in the old walled town of Faro, converted into the municipal museum.

That the last regular interment in the cemetery is dated 1932 introduces an even darker history than the Inquisition. The three families continue to live in Portugal, but they had much to endure in order to survive. The grandson of the tobacco farmer became the country’s leading heart specialist, and was present when the cemetery was reopened in 1999. This was an occasion graced by dignitaries from Israel, the Portuguese government and the United Nations.

Chiefly responsible for the reopening was a member of one of those families, then an American citizen, Isaac Bitton. On a visit to the “old country” he had come to Faro and been shocked by the decay of the cemetery. He became committed to its restoration. With the help of a builder from further along the coast he prepared plans, then set about raising funds. That he was successful is self-evident. In recognition of his work the builder became the only person to be buried in the cemetery since 1932.

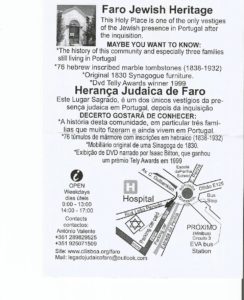

Despite this history, the site is surprisingly modest, and all the more moving for that. There are 76 adult graves with inscriptions, and a number of children’s graves marked simply by low mounds of stones. Apart from these, within the walled enclosure is an exhibition centre, where a video of Isaac Bitton’s compaign is shown, and a synagogue with furnishings of 1830. The video was awarded a prize.

Antonio gives a simple, moving description of a number of the graves, particularly the woman left to manage a family business and her only son, who died at 18. His grave is the only one we noticed with decorative carving as well as an inscription. It is visible beyond the featured grave in one of photographs. There is also the history of a one-time Portuguese consul in Bordeaux. He was Aristides de Sousa Mendes, who arrived one day at a World War II refugee centre with his family. As they were all smartly dressed the staff questioned their status. His story left them in no doubt.

At the consulate he had received many Jewish refugees from the Nazis and the Vichy regime. Despite instructions to the contrary from the Salazar government he awarded visas and enabled many to escape to the USA and elsewhere. When his actions were discovered he was dismissed and left with no income for the rest of his life. With his family he had walked to the refugee centre. He died in poverty in 1954, aged 69. A plaque beside the cemetery gate identifies him as a great humanitarian.

The cemetery is open on weekdays, from 9 am to 1 pm and from 2 pm until 5 pm. For a time of sober reflection amid the sun and pleasure of an Algarvian holiday it is highly recommended.