“See that river?” The Sergeant-Major sounded stern.

I glanced to my left and nodded. The shallow torrent was 20 metres away.

“Get in there,” the Sergeant-Major continued. “One hundred press-ups. Go! A soldier’s compass never lies.”

“Get in there,” the Sergeant-Major continued. “One hundred press-ups. Go! A soldier’s compass never lies.”

My mistake had been to report that my compass was faulty. Its needle was pointing in the wrong direction. The Sergeant-Major did not believe me, even if the device had become demagnetised. I did as a soldier would do. One hundred press-ups without protest, in an ice-cold mountain river. Unjustified punishment complete, I rose to my feet, nodded to my superior, and sought out the Quartermaster to return the device.

Although the Sergeant-Major was wrong, he was right that navigation is critical. Anyone who wishes to take to the mountains should be comfortable with finding their way.

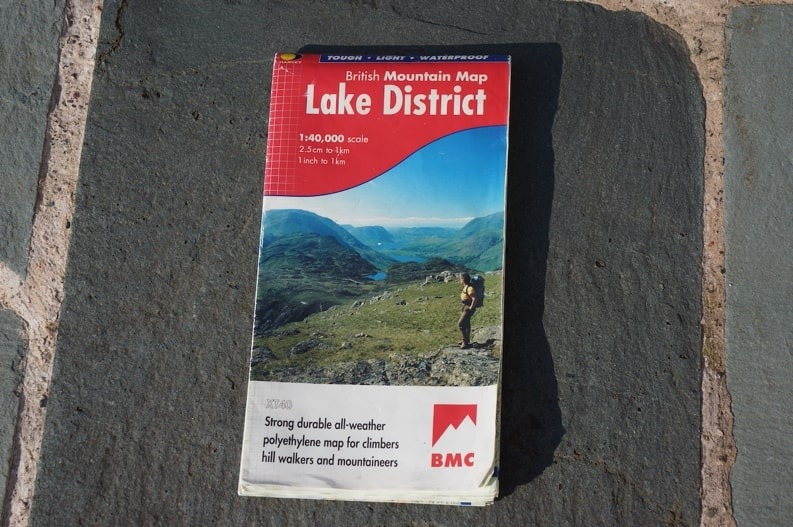

A map is essential, as is a compass. I keep both handy, although study the compass rarely, but I look at the map frequently. I ensure I know which way is north, perhaps by looking at the sun. When I study the map, I hold it with north on the map matching north on the ground. Navigators call that setting.

A map is essential, as is a compass. I keep both handy, although study the compass rarely, but I look at the map frequently. I ensure I know which way is north, perhaps by looking at the sun. When I study the map, I hold it with north on the map matching north on the ground. Navigators call that setting.

When out in the mountains, I divide my route into smaller portions, and tick off each bit once it is done. I follow walls or paths, sometimes rivers, or other linear features, using them as handrails until I reach an obvious object. Perhaps this is a wood, maybe a river bend, that tells me it is time to turn. I look at my map repeatedly and do not mind a longer route if I can avoid becoming lost.

Have I been lost? Quite often, and usually when I have been following others. The problem with being lost is admitting it, to yourself and to those around.

Have I been lost? Quite often, and usually when I have been following others. The problem with being lost is admitting it, to yourself and to those around.

“Are you OK?” I asked an elderly couple on a Lake District ridgeline the other day. I had seen them in the distance. She was waving her sticks angrily while he flapped his right hand, to stop her making a fuss.

“Fine,” the man replied. I detected doubt in his tone.

“It’s not,” the woman declared. “Charlie, ask this gentleman.”

Meekly, Charlie did, and I soon saw that the couple was on the wrong path, wrong mountain, wrong ridge, and heading in the wrong direction. Charlie had been too pig-headed to confess.

I stayed for an easy ten minutes, explaining where they should go. Charlie visibly relaxed, not helped by his wife’s I-told-you-so expression. They had taken a compass bearing before they set out, but the metal in a nearby barbed-wire fence had deflected the compass. Neither had noticed, and off they went, in completely the wrong direction. Charlie realised the error quickly but became frightened – being lost can do that – and he did what so many do in that situation. He carried on walking, straight, and with no idea of where he was headed. Perhaps he expected a Divine hand to guide him.

I stayed for an easy ten minutes, explaining where they should go. Charlie visibly relaxed, not helped by his wife’s I-told-you-so expression. They had taken a compass bearing before they set out, but the metal in a nearby barbed-wire fence had deflected the compass. Neither had noticed, and off they went, in completely the wrong direction. Charlie realised the error quickly but became frightened – being lost can do that – and he did what so many do in that situation. He carried on walking, straight, and with no idea of where he was headed. Perhaps he expected a Divine hand to guide him.

In today’s mountains, it is rare to see walkers with map and compass. Such things are seen as dated. Most use electronic technology. Mobile apps abound for navigating, as do global positioning devices, or GPS. I use both, but rarely, as they rely on batteries, which can run out, be damaged by water, and are heavy. I have drowned a mobile on a rainy Brecon Beacon, cracked another on a Peak District hillside, and pulverised a GPS in Greece. The mountains of the world are filled with my damaged technology.

Yet there is one electronic item I worship – the altimeter. Broad, circular and black, it sits snugly on my wrist and is impossible to hide.

Yet there is one electronic item I worship – the altimeter. Broad, circular and black, it sits snugly on my wrist and is impossible to hide.

“Cor, Mum!” said one little boy, out walking with his mother, as I climbed a fellside last month. “Look at that man’s watch!” The boy, who was about ten years old, pointed at my wrist. I gave a massive wink.

“It’s an altimeter,” I explained.

“What’s it do?” asked the child, while his mother looked on impatiently.

“Tells me how high I am above the sea,” I replied.

“Big deal,” said the mother disinterestedly. “Come on!” she ordered and dragged the boy behind her. I saw him scuff his feet reluctantly against any rock he could find.

I was sorry not to have given the child an explanation, as the altimeter is my Godsend for navigation. As I walk, I keep an eye on the contour lines of my map, the lines that declare the height at any point. I look at the contour and then my altimeter. Instantly, I can tell where I am.

I was sorry not to have given the child an explanation, as the altimeter is my Godsend for navigation. As I walk, I keep an eye on the contour lines of my map, the lines that declare the height at any point. I look at the contour and then my altimeter. Instantly, I can tell where I am.

As my Sergeant-Major implied, navigation is essential. Never rely on others to say where you are in the mountains. Learn how to do it yourself and think about buying an altimeter.

If you think you are lost

Becoming lost in the mountains is easy. All you need to do is to allow your mind to wander. Getting out of trouble is much harder.

You can reduce your chances of being lost by doing the following:

Leave your route with someone you trust, and who will trigger Mountain Rescue if you fail to return by a set deadline.

Take photographs as you walk, to which you can refer if required.

Look behind you from time-to-time. This will let you see your route from a different direction, should you need to retrace your steps.

Go on a navigation course.

Should the worst happen, and it will if you do sufficient mountain walking, use this mnemonic: S-T-O-P (Stop, Think, Observe, Plan)

Stop

- Sit down and have something to eat and drink. This will feel like wasted time. It is not. Recognise being lost as early as you can.

- It is common to be frightened. Remember that.

- Put on something warm.

Think (about how you got there)

- Where were you when you last knew your location? Find it on the map.

- How long and how fast have you been walking since then, and in which direction? Find your possible location on the map.

- What landmarks should you be able to see from where you are now, and in which directions?

Observe (what is around you)

- Wait for a gap in any clouds and look around. What can you see?

- If you recognise a feature, take its bearing. You will be somewhere on a line drawn from that feature. If you see two features that you recognise, you can work out your exact position.

- If you have a mobile app, look at it. Conserve your battery.

- If you have a GPS, look at it and take a grid reference. Find your position on the map. Conserve your battery.

- What does your altimeter say? Look at the contours on the map.

- If you are on a slope, in what direction is the slope facing (slope aspect)? Find likely slopes on the map.

Plan (what happens next – there are several choices)

- If you have colleagues with you, ask them what they think.

- Work out the bearing you need and walk on it. It will feel like a step into the unknown.

- Count your paces as you go – I do 65 double paces for every 100 metres. You should know this number for yourself before you go near a mountain.

- Aim for a linear feature – ridge, wall, river, path, road – and follow it.

- Break the route down into small portions. Treat each portion as a separate journey.

- Return to your last known point.

- Follow a stream downhill – not as safe as it sounds – it may go over a waterfall.

If you are completely stuck, whatever the reason, consider these options:

Blow your whistle – there are two systems:

- six blasts on your whistle, repeated every minute. A reply is three whistle blasts.

- three blasts on your whistle, each blast lasting three seconds and repeat every minute.

Be prepared to spend the night where you are and wait until morning. Do not sleep beside a river as its noise will prevent you from hearing any rescuers. Display bright items for others to see.

Call for help if you have power and signal (999 in UK, 112 in Europe, 911 in USA, 000 in Australia). If you summon the Emergency Services (Mountain Rescue), be prepared with the information they will need in case they are unable to ring you back.

The details are:

- your location and the weather

- nature of the predicament or casualty

- number and age of people in your party

- colour of clothing and equipment you and your party possess

- any medical conditions you know about

- registration numbers of your vehicles and where they are parked

Trigger your personal locator beacon, if you have one.

I carry the following items to help me with navigation

GPS device

Garmin Oregon 650

Compass

I use a Silva Expedition 4 compass, as this is light, has various scales I can use to measure maps, and a magnifying glass when my eyesight is misbehaving.

Altimeter

Suunto Core

Map (as appropriate)

I prefer a 1:25,000 scale for walking, although 1:40,000 gives me a good overview of an area.

Mobile app

I use Gaia GPS but there are many others from which to choose.

Personal locator beacon

I do not carry a Personal Locator Beacon, but if you wish to consider this, have a look at the Garmin inReach, which allows you to navigate, stay in touch globally, and trigger an SOS if need be. It will require a satellite subscription. See discover.garmin.com/en-GB/inreach/personal

Navigation courses:

Complete navigation skills

My favourite shops for outdoor devices are:

Cotswold Outdoor

More information

5 ways to improve your navigation skills