A journey to the nuclear Exclusion Zone and a place frozen in time

81 year-old Ivan Semenyuk needs a stick to help him walk these days. He stoops a little and struggles to pick up the logs from the wood store outside his humble home, especially in the depths of a Ukrainian winter.

Inside, we help him light the stove and settle back to hear his story. Because Ivan is still living in the village of Paryshyv, deep within the official Exclusion Zone of Chernobyl, where – at 01:23 on 26th April, 1986 – reactor number 4 at the nearby nuclear plant exploded.

Inside, we help him light the stove and settle back to hear his story. Because Ivan is still living in the village of Paryshyv, deep within the official Exclusion Zone of Chernobyl, where – at 01:23 on 26th April, 1986 – reactor number 4 at the nearby nuclear plant exploded.

It is rumoured that designers knew of a fault with rods inserted into the reactor heating it up, rather than cooling it down, when trying to avert problems during a safety test.

It has been reported that 28 people died in the immediate aftermath, one employee from the blast and one from a fatal dose of radiation, the others mainly firefighters and employees.

And it is believed that, out of 600,000 ‘liquidators’ subsequently involved in the clean-up operation, many have since died prematurely from radiation, or from related diseases.

But nobody really knows what happened that catastrophic night, or how many people have died in the years since, as a direct result of the thermal explosion. For Chernobyl, in Ukraine and close to the Belarus border, was part of Gorbachev’s Soviet Union and the regime did all it could to suppress the true extent of the disaster from both the local community and from the outside world.

For inquisitive Silver Travellers more interested in history, experiences and different cultures than ‘fly ‘n’ flop’ holidays, this short Discover Chernobyl break from Explore will expose you – safely – to this fascinating piece of history and surreal environment.

You will hear how, because of the wind direction in the days after the explosion, airborne radiation was detected by 30 countries across Europe. Only then did the Soviet authorities take appropriate action around Chernobyl, scientists deciding on an outer 30 kilometre Exclusion Zone, requiring the evacuation of 91,000 people from 76 villages between 27th April and 7th May.

You will hear how, because of the wind direction in the days after the explosion, airborne radiation was detected by 30 countries across Europe. Only then did the Soviet authorities take appropriate action around Chernobyl, scientists deciding on an outer 30 kilometre Exclusion Zone, requiring the evacuation of 91,000 people from 76 villages between 27th April and 7th May.

Ivan and his family were forcibly evicted from their home during this initial phase. But he returned a year later in 1987, since when he has been living off-grid as a ‘self-settler’ in Paryshyv. His wife died a year ago. His two children live elsewhere. Faded family photographs sit inside a blue frame, on the wall above a cluttered table. Only two other women now live in the village, but Ivan rarely sees them, especially in the freezing Ukrainian winter. He admits he is lonely and welcomes us, his first visitors for a few days.

Wood absorbs radiation, so in the immediate aftermath of the explosion most houses inside the Exclusion Zone were burned down, together with all the trees in this densely forested area, and buried in the ground. Ivan’s home is more solid, and was spared. Today, he is almost free of radiation and spends his days tending to the chickens, sorting out the fire and cooking, mainly outside. Surprisingly perhaps, the Exclusion Zone is a fertile area, and shrubs, flowers and herbs in his garden will thrust their way upwards when spring comes. And wildlife thrives too, thanks to the shortage of human presence.

Wood absorbs radiation, so in the immediate aftermath of the explosion most houses inside the Exclusion Zone were burned down, together with all the trees in this densely forested area, and buried in the ground. Ivan’s home is more solid, and was spared. Today, he is almost free of radiation and spends his days tending to the chickens, sorting out the fire and cooking, mainly outside. Surprisingly perhaps, the Exclusion Zone is a fertile area, and shrubs, flowers and herbs in his garden will thrust their way upwards when spring comes. And wildlife thrives too, thanks to the shortage of human presence.

You need an authorised guide to visit the strictly controlled Exclusion Zone, and over two days you will be shown sites that provide a snapshot of a place frozen in time, and giving a real sense of life under Soviet control.

Erected in 1970, ‘Duga’ was a secret early warning radar system for Cold War detection of ballistic missile launches from China and the USA. Masquerading on the map as a children’s summer camp, 1,200 people lived on site, 600 of them working around the clock on the vast Meccano-like construction, disappearing into the murky winter sky above us. It was also known as ‘Chernobyl 2’ and the ‘Russian Woodpecker’, after the distinctive, repetitive tapping noises emitted without warning to the outside world.

Erected in 1970, ‘Duga’ was a secret early warning radar system for Cold War detection of ballistic missile launches from China and the USA. Masquerading on the map as a children’s summer camp, 1,200 people lived on site, 600 of them working around the clock on the vast Meccano-like construction, disappearing into the murky winter sky above us. It was also known as ‘Chernobyl 2’ and the ‘Russian Woodpecker’, after the distinctive, repetitive tapping noises emitted without warning to the outside world.

We see abandoned Lada cars, deserted kindergarten schools, cartoon-covered shacks in a woodland camp, and tear-inducing memorials.

But perhaps the most haunting image is walking through the ‘ghost town’ of Pripyat, reached via the ‘Bridge of Death.’ The closest community to the nuclear plant, people heard the explosion and were told it was safe to watch the conflagration from the bridge. It wasn’t. Most were badly contaminated and subsequently died.

Built in 1970 as a model Soviet community, by 1986 close to 50,000 people lived in Pripyat, including 6,500 children. Most worked at Chernobyl, as engineers or scientists, and the town’s average age was just 26. The imposing Communist Party HQ dominates the main square. At one of the schools, some of the main walls collapsed a few years ago. Trees now grow on what was the football stadium pitch, but the grey concrete stand remains intact. A couple of retro shopping trolleys lay in rubble and dust from one of the Soviet Union’s first supermarkets. And at the hospital, our guide shows us a scrap of a fireman’s skull-cap. The basement was the most contaminated area, as this was where the firemen attending the explosion were first treated. In the immediate aftermath, the cap registered 7,000 Sieverts. A scrap of its material has since been brought up to the ground floor of the rubble-strewn hospital. On the day we visited, the reading was 55 Sieverts.

Built in 1970 as a model Soviet community, by 1986 close to 50,000 people lived in Pripyat, including 6,500 children. Most worked at Chernobyl, as engineers or scientists, and the town’s average age was just 26. The imposing Communist Party HQ dominates the main square. At one of the schools, some of the main walls collapsed a few years ago. Trees now grow on what was the football stadium pitch, but the grey concrete stand remains intact. A couple of retro shopping trolleys lay in rubble and dust from one of the Soviet Union’s first supermarkets. And at the hospital, our guide shows us a scrap of a fireman’s skull-cap. The basement was the most contaminated area, as this was where the firemen attending the explosion were first treated. In the immediate aftermath, the cap registered 7,000 Sieverts. A scrap of its material has since been brought up to the ground floor of the rubble-strewn hospital. On the day we visited, the reading was 55 Sieverts.

Silver Travellers interested in this intriguing travel experience need not worry about nuclear contamination. You will be tested for radiation levels throughout your stay in the Exclusion Zone, where – strangely – ambient readings are less than in Kyiv, 2 hours further south. And it’s ‘fun’ to carry a portable dosimeter around abandoned villages, searching for radiation hot-spots that might trigger the alarm as the Sieverts jump from 0.14 to a beeping 6.0 or 7.0.

Silver Travellers interested in this intriguing travel experience need not worry about nuclear contamination. You will be tested for radiation levels throughout your stay in the Exclusion Zone, where – strangely – ambient readings are less than in Kyiv, 2 hours further south. And it’s ‘fun’ to carry a portable dosimeter around abandoned villages, searching for radiation hot-spots that might trigger the alarm as the Sieverts jump from 0.14 to a beeping 6.0 or 7.0.

Our guide explains that the length of time you’re exposed to radiation is more important than the absolute level of Sieverts. 4,000 people still work at Chernobyl, maintaining the site. Everyone is limited to two weeks in the Exclusion Zone, before having to leave for another two weeks. And it will take 24,000 years for the plutonium to completely disappear from the Chernobyl site.

A ‘Special Zone’ exists around the nuclear reactors, but we got surprisingly close to number 4. Encased in a concrete sarcophagus since the end of 1986, it was protected anew a couple of years ago by a French-designed stainless steel outer shell, 10 years in the making, the largest movable structure ever made and hopefully capable of containing Chernobyl’s nuclear contamination for another 100 years.

The trip also includes a full day exploring Kyiv, the beautiful ancient capital of Ukraine situated on the Dnipro River. You’ll see historic Golden Gate, once the main entrance to the city; the onion-domed Santa Sophia cathedral; the baroque church of Saint Andrew; and the Lavra Historical & Cultural Reserve, a walled monastic city rivalling Jerusalem and Greece’s Mount Athos in Orthodox Christian religious significance, and home to the remarkable 11th century ‘Monastery of the Caves’.

The trip also includes a full day exploring Kyiv, the beautiful ancient capital of Ukraine situated on the Dnipro River. You’ll see historic Golden Gate, once the main entrance to the city; the onion-domed Santa Sophia cathedral; the baroque church of Saint Andrew; and the Lavra Historical & Cultural Reserve, a walled monastic city rivalling Jerusalem and Greece’s Mount Athos in Orthodox Christian religious significance, and home to the remarkable 11th century ‘Monastery of the Caves’.

You will also get a good sense of more modern influences on the city and on the country: grey Soviet-built low-ceilinged apartment blocks, freezing cold in winter and furnace-hot in the summer; the awe-inspiring Mother Motherland statue, reaching 100 metres into the grey sky to honour the heroes of the Soviet Union; and Revolution Square, commemorating historical freedom and the 2014 ‘Revolution of Dignity’ when Ukrainians reignited their independence to oust the Moscow-sponsored President.

You will also get a good sense of more modern influences on the city and on the country: grey Soviet-built low-ceilinged apartment blocks, freezing cold in winter and furnace-hot in the summer; the awe-inspiring Mother Motherland statue, reaching 100 metres into the grey sky to honour the heroes of the Soviet Union; and Revolution Square, commemorating historical freedom and the 2014 ‘Revolution of Dignity’ when Ukrainians reignited their independence to oust the Moscow-sponsored President.

And in the Chernobyl Museum you will begin to learn what happened that fateful morning of 26th April, 1986, before visiting the Exclusion Zone yourself. The graphic of the wind blowing the resulting radiation across Europe in the days after the explosion is mesmerising.

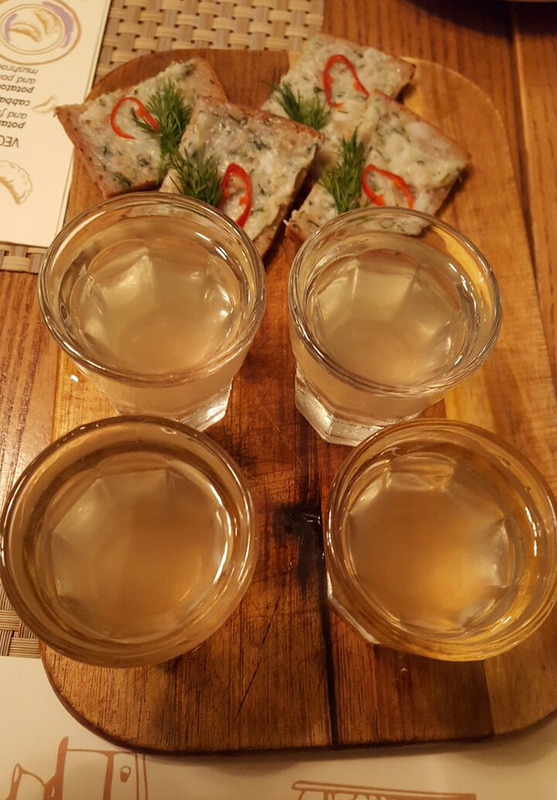

Inquisitive Silver Travellers interested in understanding more about Chernobyl, and also seeing at first hand how a former Republic of the Soviet Union is surviving independently, will really enjoy this trip. Accommodation, even the hostel inside the Exclusion Zone, is good and Ukrainian food and drink – including lard, dumplings, horseradish vodka and chicken Kiev – will provide fuel for your nuclear adventure.

But it is the human side of Chernobyl that will linger most in my memory. I hope Ivan is keeping warm.

More information

Explore (01252 884 723; explore.co.uk) offers a four-night Discover Chernobyl short break that combines three nights in Kiev with a night within the Exclusion zone. From £829 per person including flights, some meals, an Explore tour leader and an official Exclusion Zone guide.

An amusement park in Pripyat, due to open on May Day in 1986, lays abandoned but is still eerily intact.