Why it’s never too late for a Remembrance holiday

Standing on the rim of La Grande Mine, I can’t help feeling that the label for this huge crater is something of an understatement. Hollowed out of Picardy’s fragile earth, the gaping hole at La Boisselle in the Somme measures a staggering 91 metres across and 21 metres deep. Whatever conversation you’re having as you approach the duckboard perimeter, you’ll stop it for sure as you peer down the steep grassy sides.

Today the chasm dubbed Lochnagar Crater is surrounded by peaceful farmland, a sobering free visitor attraction owned by Englishman Richard Dunning. But when the British blew up German fortifications here in 1916, the resulting explosion remained the loudest noise heard until Hiroshima. Quite a thought to carry with you as you tour Picardy’s tranquil, verdant countryside.

Today the chasm dubbed Lochnagar Crater is surrounded by peaceful farmland, a sobering free visitor attraction owned by Englishman Richard Dunning. But when the British blew up German fortifications here in 1916, the resulting explosion remained the loudest noise heard until Hiroshima. Quite a thought to carry with you as you tour Picardy’s tranquil, verdant countryside.

We’ve heard a lot about World War I in the last three years as many nations commemorate the centenary of the war that was supposed to end all wars. We look back at the sites and sacrifices of a vanished generation as we watch ceremonies on television, and maybe we’re inspired to delve a little deeper into our family albums and archives. So why bother to visit when TV and the internet can bring the whole sorry saga vividly to life in our own homes? Are the battlefields and cemeteries of Ypres, Passchendaele and the Somme really the stuff of which holidays are made?

Most definitely. Nobody has successfully invaded British shores since 1066, but the war zone of Northern France and Belgium is where our recent history comes to life through the death of our own. And as we enter the last year of centenary events in 2018, there has never been a more poignant time to visit with a number of new museums, memorials and exhibitions.

Travel independently by car and within an hour of Calais, you are deep in the heart of the battlegrounds of Nord-Pas de Calais. Less than two hours and you can be exploring the countryside of Flanders in one direction or Picardy’s valley of the Somme in the other; a little further south and you’re on the notorious ridge of the Chemin des Dames or the battlefields of the Marne in Champagne-Ardenne.

Travel independently by car and within an hour of Calais, you are deep in the heart of the battlegrounds of Nord-Pas de Calais. Less than two hours and you can be exploring the countryside of Flanders in one direction or Picardy’s valley of the Somme in the other; a little further south and you’re on the notorious ridge of the Chemin des Dames or the battlefields of the Marne in Champagne-Ardenne.

There are so many commemorative sites here that it’s easy to slot a few visits into a touring holiday. There’s a wealth of free information available at local tourist offices and museums, as well as self-drive themed trails. And because the concentration of sites is so great, you can easily combine Remembrance sites with cultural visits, city stays, and outdoor fun.

The coast of Nord-Pas de Calais and Picardy – now amalgamated into the new French region of Hauts de France – is packed with possibilities for water sports and beach activities, whilst inland there are hiking and walking trails suitable for both Silver Travellers and three-generational groups. Or why not combine a tour of the champagne houses with a few Great War sites? Many of our children and grandchildren have learnt about World War I at school – probably more than we did – and Remembrance visits can bring those classroom lessons zinging vividly to life.

The coast of Nord-Pas de Calais and Picardy – now amalgamated into the new French region of Hauts de France – is packed with possibilities for water sports and beach activities, whilst inland there are hiking and walking trails suitable for both Silver Travellers and three-generational groups. Or why not combine a tour of the champagne houses with a few Great War sites? Many of our children and grandchildren have learnt about World War I at school – probably more than we did – and Remembrance visits can bring those classroom lessons zinging vividly to life.

If you want to go into an area or campaign in greater depth, join an escorted tour with expert guidance from a specialist tour operator such as Silver Travel Advisor partner, Shearings Battlefield Tours. Whichever option you choose, you’ll be surprised and moved by a wealth of detail you could never have imagined.

In the area around Bethune and Vimy in Pas-de-Calais, for instance, I was humbled not only by how many nations were represented – English, French, German and Canadian of course – but also how many unexpected nationalities. At Richebourg, The Indian Memorial is flanked by tigers and lists more than 4,000 men down to the mulateers, whilst the nearby Portuguese National Cemetery is the sole place of remembrance for Portuguese soldiers lost in the Great War. And at Neuville-Saint-Vaast stands the Czechoslovak Cemetery and Memorial.

In the area around Bethune and Vimy in Pas-de-Calais, for instance, I was humbled not only by how many nations were represented – English, French, German and Canadian of course – but also how many unexpected nationalities. At Richebourg, The Indian Memorial is flanked by tigers and lists more than 4,000 men down to the mulateers, whilst the nearby Portuguese National Cemetery is the sole place of remembrance for Portuguese soldiers lost in the Great War. And at Neuville-Saint-Vaast stands the Czechoslovak Cemetery and Memorial.

But one of the newest attractions makes no distinction by nationality or rank. The stunning Ring of Remembrance – L’Anneau de la Mémoire – near the French National cemetery of Notre Dame de Lorette lists nearly 580,000 soldiers who fell in Pas de Calais in simple alphabetical order.

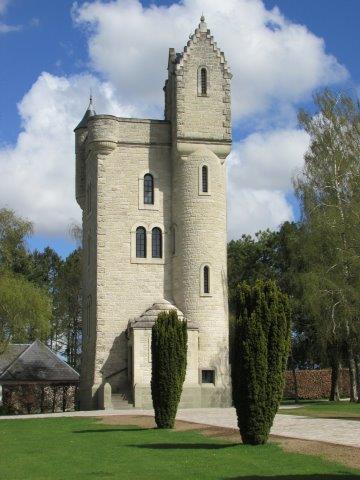

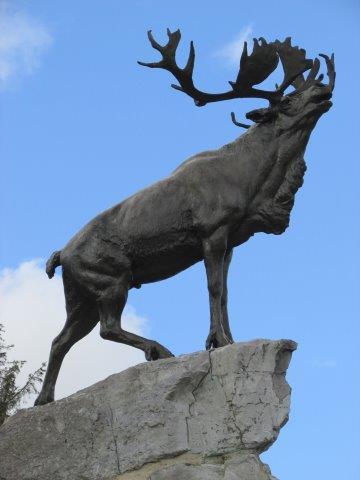

I’ve stood in silence too before beautiful statues that personify national pride. Who’d have expected the figure of a man from French Basque country facing away from the battlefields of the Chemin des Dames in Picardy? Or the magnificent caribou on top of the Newfoundland Memorial which dominates the grass-lined trenches of the Canadian cemetery at Beaumont Hamel? Just a short walk away stands a small dead tree – last one standing from the battlefield – with flags and poppies at its foot.

I’ve stood in silence too before beautiful statues that personify national pride. Who’d have expected the figure of a man from French Basque country facing away from the battlefields of the Chemin des Dames in Picardy? Or the magnificent caribou on top of the Newfoundland Memorial which dominates the grass-lined trenches of the Canadian cemetery at Beaumont Hamel? Just a short walk away stands a small dead tree – last one standing from the battlefield – with flags and poppies at its foot.

No-one who has read Sebastian Faulk’s unforgettable novel Birdsong can forget his evocative depictions the men who tunnelled beneath enemy lines to lay explosives such as La Grande Mine. And no television experience could reproduce how I felt at walking inside La Butte de Vauquois near Verdun, where French and German soldiers lived like moles for three-and-a-half years on opposite sides of this strategic hill. Nor on the outskirts of Arras, the emotions I felt on a guided tour of the Wellington Quarry. Allied soldiers lived in this makeshift underground town before emerging in darkness before enemy lines in 1917. Stand by the exit sign pointing up to the unknown and I challenge you not to feel a pang. But it’s uplifting too – a testimony to human spirit and the fight for freedom.

Every site offers a different perspective and it’s hard to pick favourites. Amongst the major players, I’m constantly moved by Lutyens towering memorial at Thiepval, visible from far and wide. Don’t miss Thiepval’s excellent new visitor centre full of moving memorabilia, nor the Historial de la Grande Guerre at nearby Peronne. The huge hidden bunker of La Coupole near Saint Omer is always sobering too, built to launch V2 rockets on London and a chilling reminder of what might have been.

Every site offers a different perspective and it’s hard to pick favourites. Amongst the major players, I’m constantly moved by Lutyens towering memorial at Thiepval, visible from far and wide. Don’t miss Thiepval’s excellent new visitor centre full of moving memorabilia, nor the Historial de la Grande Guerre at nearby Peronne. The huge hidden bunker of La Coupole near Saint Omer is always sobering too, built to launch V2 rockets on London and a chilling reminder of what might have been.

But it’s often the smaller and the unexpected that move me. The surprise view over the Somme water meadows from the small hill at Frise, where information panels describe a bloody battle in this now idyllic landscape. The inscription on the headstone of a fallen 17-year-old from Yorkshire at Bethune – ‘It is well with the lad. Mother’. And those poignant last letters from the trenches, full of optimism, and donated to museums by bereft family members.

Last spring, I spent a night at Butterworth Farm, a charming B&B with self-catering option in the village of Pozieres, run by local mayor Bernard and his wife, Marie. They named the property after English composer and musician George Butterworth, who died somewhere in the field behind their home in August 1916, aged just 31. They’ve even erected a small brick memorial to the fallen Englishman beside their front gate with support from the Commonwealth War Graves commission.

Last spring, I spent a night at Butterworth Farm, a charming B&B with self-catering option in the village of Pozieres, run by local mayor Bernard and his wife, Marie. They named the property after English composer and musician George Butterworth, who died somewhere in the field behind their home in August 1916, aged just 31. They’ve even erected a small brick memorial to the fallen Englishman beside their front gate with support from the Commonwealth War Graves commission.

Today we remember George Butterworth – a young talent so sadly lost – through his popular orchestral idyll The Banks of Green Willow. And now, whenever I hear his music, I also remember the kindness of a French family who took him to their hearts. And I’m glad that, 100 years on, Remembrance tourism reaches out to all of us.